Getty Images spent millions pursuing Stability AI through UK courts. They had evidence. Stability AI even admitted to using Getty's images to train Stable Diffusion. Yet last week, Getty lost the lawsuit.

The reason? A single technical determination: AI models don't actually "store" the images they're trained on. They learn patterns from them and compress those patterns into mathematical relationships. The originals are not retained in any shape or form by the model.

Two months earlier, across the Atlantic, Anthropic wrote a $1.5 billion check to settle a similar dispute. Authors discovered the company had downloaded over 7 million pirated books from sites like Library Genesis to train its Claude chatbot, paying roughly $3,000 per book for about 500,000 works. The judge ruled that training on legally purchased books was fine, but downloading pirated copies crossed the line.

Here's where it gets interesting. In both cases, the AI companies admitted to using copyrighted material. But one walked away largely vindicated, while the other paid what lawyers called "the largest copyright recovery in history." The difference? Not what they learned from, but how they obtained it.

Which raises an uncomfortable question nobody wants to answer: If AI learns like humans learn, why should it need different rules? And if it should have different rules, who defines them and what triggers them?

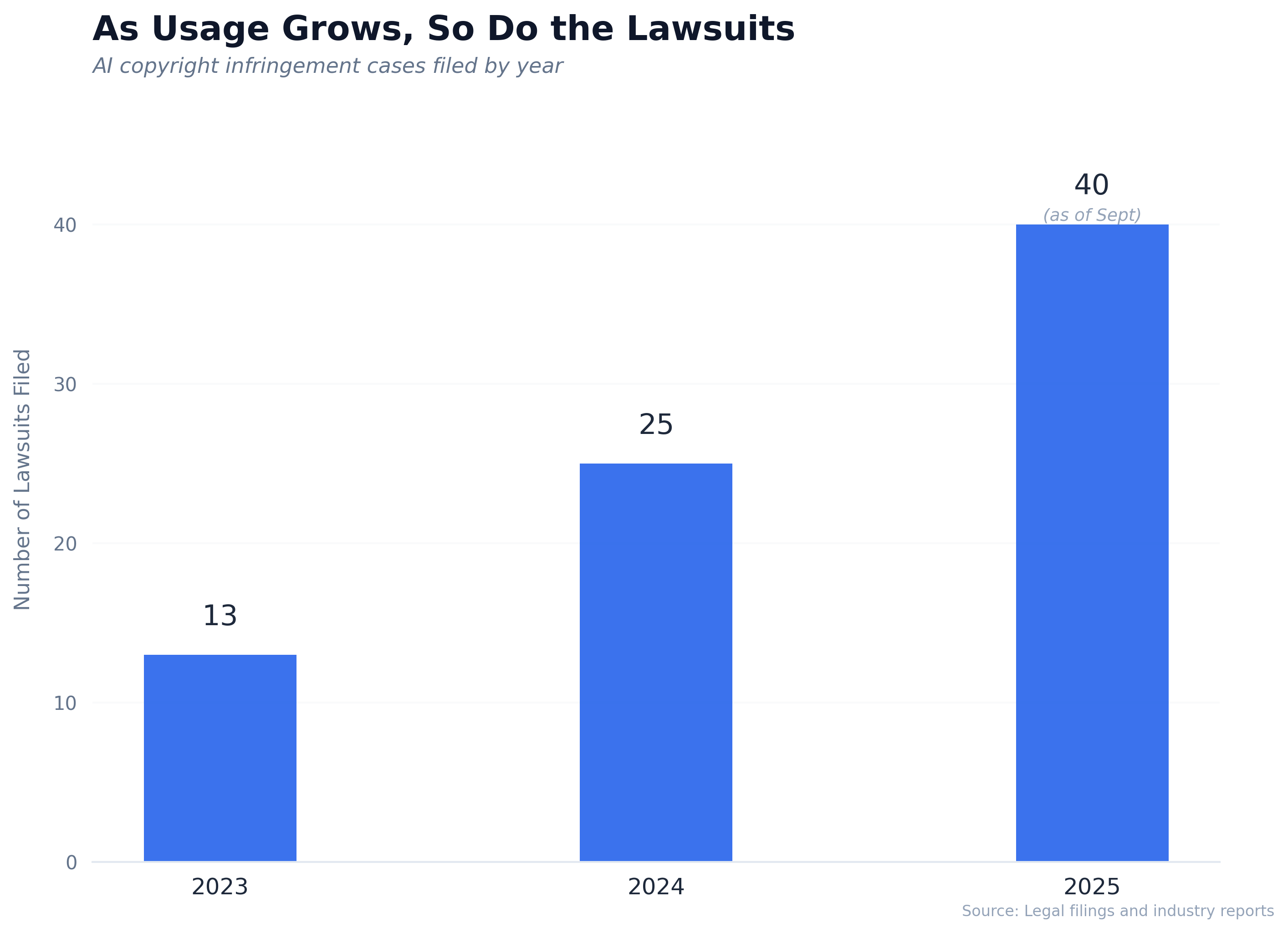

The lawsuit numbers are telling.

The Learning Paradox

Think about how you learned to write. You read thousands of lines, absorbed sentence patterns, picked up vocabulary, and internalized what makes an argument compelling. Your brain compressed all that exposure into what we call "writing ability." You can't reproduce the exact articles you learned from (unless you memorized them), but their influence is baked into how you construct sentences.

The UK judge in the Getty case ruled that AI model weights "store nothing" and "reproduce nothing"—they're just "the product of patterns and features learned during training."

Sounds reasonable. Except research shows otherwise. The New York Times famously got ChatGPT to spit out verbatim copies of their articles.

So which is it? Are AI models learning abstract patterns, or are they sophisticated copy machines?

The answer: both, depending on the data. Memorization happens overwhelmingly when training data includes multiple copies of the same work. Famous images or frequently repeated text get "known" well enough to reproduce with high fidelity. This is why DALL-E can reproduce Studio Ghibli–like images closely, but not something by Vincent van Gogh.

This is where Getty's case fell apart. The model couldn't produce perfect Getty images on command. But doesn't that create a perverse incentive? Better engineering—clean data, proper training techniques—means less memorization, which means better legal protection.

The law is essentially saying: if you're good enough at compression that we can't detect copying, you're fine. If your copying is detectable, you're liable.

Does that make sense as a legal standard?

The Real Problem

Courts can't solve this problem—they lack the necessary tools.

If Getty, with its millions in legal resources and documented evidence, can't win, what chance do individual creators have?

Until we establish laws that define what's acceptable in AI training, these disputes will keep multiplying. We need clear definitions: who owns what, what can be used, and what can be reproduced. These definitions will shape how the entire ecosystem develops.

Right now, we're forcing 21st-century learning machines into 19th-century copyright frameworks. These frameworks weren't designed for AI. They were created for an era when information was scarce. Copyright laws assume copying is discrete and detectable—that you can point to specific reproductions. They struggle with "learning" as a process that simultaneously does and doesn't involve copying.

The market is already adapting to this uncertainty. OpenAI signs deals with publishers. Anthropic settles for $1.5 billion. Getty licenses its images to "leading technology innovators" while suing others. Companies large enough to absorb litigation risk move forward; everyone else hedges.

But licensing frameworks built on fear aren't the same as clear legal rules. And builders need clear rules.

The Unanswerable Question

So back to the core tension: should AI models follow different rules than human learners?

I've talked to many people in the industry, and no one has a clear answer. Depending on who you ask, responses fall into three buckets.

- Yes, because scale matters. A human might read 10,000 books in a lifetime. An AI ingests millions in days. That quantitative difference becomes qualitative—it's not learning anymore, it's industrial-scale pattern extraction. Different scale, different rules.

- No, because learning is learning. If the process is genuinely transformative—if the AI can't reproduce your specific work on demand—then it learned from you the same way a student learns from a teacher. We don't require students to license every book they read.

- Maybe, depending on reproducibility. If the model memorizes and can regurgitate your work, that's copying. If it only learns patterns, that's fair use. This is roughly where courts are landing, but it means better compression technology equals better legal protection. Which feels backward.

The Getty judgment said AI models don't store data if they can't reproduce it. The Anthropic settlement said the source of training data matters more than the training itself. Both cases left the fundamental question unanswered.

Builders have operated in ambiguity before AI, but AI complicates matters exponentially. GPT-4 was trained on roughly 13 trillion tokens—equivalent to billions of books. A prolific human reader might absorb a few thousand books in a lifetime.

Not everyone can argue copyright law. But all of us learn, and we learn much the same way AI does. The core argument is whether learning itself—absorbing patterns from the world and using them to create something new—can be owned. To me, that's a philosophical question dressed up as a legal one.

Here is a question for you.

What are your thoughts about this issue? Is it legal? Is it moral? Or neither?

Write to us at plainsight@wyzr.in. We will include the best responses in our following editions.

Subscriber Spotlight

Raghuveer Dinavahi shared a wonderful response on our edition, Stuck in Second Gear:

Great article! The line lands well, "The fastest way forward is not more speed, but fewer vehicles" and fewer tools. When too many things are crowding the life lane, one thing that I've been trying to practice is to just pause everything. And once overwhelm settles, see if I can take one resonant step forward, a very small one, an then celebrate the step. That could be a click, something that I'm at least mildly drawn to, and then maybe follow another click. Slowly that builds momentum to get the activity ball rolling.

What we’re reading this week

Made to Stick by Chip and Dan Heath

Clear communication matters in every profession. This book takes a fresh look at clichés, offering surprising new perspectives on old communication wisdom.

Best,